Down @ the

Crossroads w/ Dylan, Robert Johnson and the Devil

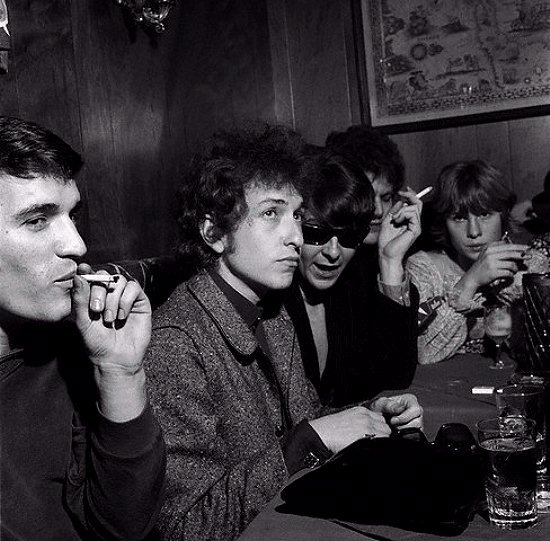

The day Bob Dylan signed his first Columbia

recording contract in John Hammond, Sr.’s office Hammond gave Dylan a couple of

albums of other Columbia artists including Robert Johnson’s “The King of the

Delta Blues,” who Dylan never heard of

but blew him away.

The Mississippi Delta is the home and cradle of the

blues as much as New Orleans is the birthplace of jazz, and in academic circles

blues is considered a branch of jazz, and in fact followed the jazz trail when

the musicians and prostitutes were kicked out of New Orleans in the closure of

Storyville, the once-legal red light neighborhood where they lived, by the U.S.

Army and Navy, though the righteous citizens of the city protested. “You can

make it illegal but you can’t make it unpopular,” the New Orleans mayor said.

But just as Katrina did a century later, the civic crackdown on Storyville – in

November 1917, spread the musicians and the music beyond the city limits, and

most of the suddenly out-of-work musicians followed the riverboats upriver to

St. Louis, Memphis and Chicago, and letting off the bluesmen in the delta where

they took root.

Their contemporary offshoots include the likes of

Sonny Boy Williamson, James Cotton, B.B. King, Levon Helm and Robert Johnson –

the “King of the Delta Blues,” who died broke and friendless at 27 years, said

to be poisoned by a jealous husband or lover, leaving behind only 20 some

recorded songs and two photographs.

When John Hammond, Sr. and Allan Lomax tried to find

him to record him he was already dead, but not forgotten.

Legend has it that Robert Johnson couldn’t play a

lick when he first picked up a guitar as a young boy, and was the subject of

jokes among the real musicians, until he left town for awhile and came back

with a style that shocked and amazed everyone, sparking a the myth that he made

a deal with the devil, selling his soul in exchange for the musical talent.

“Sweet Home Chicago” was one of the songs Johnson

recorded in two sessions at Texas hotels, and his other songs were covered by

many artists over the years, but his most famous song is “Crossroads Blues”

that Eric Clapton, Stevie Ray Vaughn, Jimi Hendrix and dozens of others have

covered and made famous.

According to Dylan, Robert Johnson hit him like a

“tranquilizer bullet.”

Dylan later wrote in his autobiographical

Chronicles, Volume 1: “I listened to it repeatedly, cut after cut, one song

after another, sitting staring at the record player. Whenever I did, it felt

like a ghost had come into the room; a fearsome apparition…masked the presence

of more than twenty men….Johnson’s words made my nerves quiver like piano

wires. They were so elemental in meaning and feeling and gave you so much of

the inside picture…..There’s no guarantee that any of his lines either

happened, were said, or even imagined…I copied Johnson’s words down on scraps

of paper so I could more closely examine the lyrics and patterns and free

associations that he used, the sparkling allegories, big-ass truths wrapped in

the hard shell of nonsensical abstraction – themes that flew through the air

with the greatest of ease. I didn’t have any of these dreams or thoughts but I

was going to acquire them. I thought about Robert Johnson a lot, wondered who

his audience could have been. It’s hard to imagine sharecroppers or plantation

field hands at hop joints, relating songs like these. You have to wonder if

Johnson was playing for an audience that only he could see, one off in the

future.”

Dylan discounts “the fast moving story going around

that he had sold his sold to the devil at a four way crossroads at midnight and

that’s how he got to be so good. Well, I don’t know about that. The ones

who knew him told a different tale and

that was that he had hung around some older blues players in rural parts of

Mississippi, played harmonica, was rejected as a bothersome kid, that he went

off and learned how to play guitar from a farmhand named Ike Zinnerman, a

mysterious character not in any of the history books.”

“This makes more sense,” says Dylan, as “John

Hammond had told me that he thought Johnson had read Walt Whitman. Maybe he

did, but it doesn’t clear up everything…..I would see Johnson for myself in

eight seconds worth of 8-millimeter film shot in Ruleville, Mississippi, on a

brightly lit afternoon street by some Germans in the late 1930s, but slowing

the eight seconds, you can see that it really is Robert Johnson, has to be –

couldn’t be anyone else.”

“I wasn’t the only one who learned a thing or two

from Robert Johnson’s compositions,” Dylan wrote, “Johnny Winter, the

flamboyant Texas guitar player born a couple of years after me, rewrote

Johnson’s song about the phonograph, turning it into a song about a television

set. Robert Johnson would have loved that. Johnny by the way recorded a song of

mine, ‘Highway 61 Revisited,’ which itself was influenced by Johnson’s writing.

It’s a strange the way circles hook up with themselves. Robert Johnson’s code

of language was nothing I’d heard before or since. To go with that, someplace

along the line Suzie (Rotolo) had also introduced me to the poetry of French

symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud. That was a big deal too. I came across one of

his letters called ‘Je est un autre,’ which translates into ‘I is someone

else.’ When I read those words bells went off. It made perfect sense….I went

right along with Johnson’s dark night of the soul…Everything was in transition

and I was standing in the gateway. Soon I’d step in heavy loaded, fully alive

and revved up. Not quite yet though.”

And so it was when Hollywood came calling for the

movie rights to the P. F. Kluge novel “Eddie & the Cruisers,” and the producers

and script writers would eliminate a chapter, the one where the Cruisers drive

their ’57 Chevy to Camden to visit Walt Whitman’s house, and in its place

Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass” and “singing

the body electric” is replaced by Arthur Rimbaud, who reportedly faked his own

death in order to live out his life

anonymously, much like Eddie Wilson does in the follow up film.

Is Dylan pulling our leg with the Ike Zinnerman

story, a farmhand teaching Robert Johnson how to play guitar instead of making

a deal with the devil at the crossroads? After all, Dylan’s real name is Robert

Zimmerman.

Supporting Dylan’s version, over the popular myths

and legends, is the fact that the devil isn’t mentioned in the lyrics of Robert

Johnson’s song “Crossroads Blues,” that makes no reference to a deal with the

devil.

Cross

Road Blues

I

went to the crossroad

fell

down on my knees

I

went to the crossroad

fell

down on my knees

Asked

the Lord above "Have mercy, now

save

poor Bob, if you please

Mmmmm,

standing' at the crossroad

I

tried to flag a ride

Standin'

at the crossroad

I

tried to flag a ride

Didn't

nobody seem to know me

everybody

pass me by

Mmm,

the sun goin' down, boy

dark

gon' catch me here

oooo

ooee eeee

boy,

dark gon' catch me here

I

haven't got no lovin' sweet woman that

love

and feel my care

You

can run, you can run

tell

my friend-boy Willie Brown

You

can run, you can run

tell

my friend-boy Willie Brown

Lord,

that I'm standin' at the crossroad, babe

I

believe I'm sinkin' down

According to the popular legend: “A crossroads or

an intersection of rural roads is one of the few landmarks in

the Mississippi Delta, a flat featureless plain between the Mississippi

and Yazoo rivers. It is part of the local iconography. A crossroads is also

where cars are more likely to slow down or stop, thus presenting the best

opportunity for a hitchhiker. In the simplest reading, Johnson describes his

grief at being unable to catch a ride at an intersection before the sun sets. However,

many see different levels of meaning and some have attached a supernatural

significance to the song.”

Crossroads are also points where people, families,

towns, cities and sometimes whole societies reach a point in time where life

changing decisions must be made, directions are changed and new destinations

are set.

And so it came to pass in the summer of 1965 when America’s

national psych came to a crossroads that was a circle – the Somers Point, New

Jersey circle that led to many directions, five different roads, each with its

hazards and rewards.

Some people want to know why the summer of ’65 was the

best tourist season the Jersey Shore has ever seen before or since. Families

came, college kids made it cool, hippies thought it was hip, bikers put in an

appearance, but as everyone who was there remembers, it was The Place to be at

that time. Some say it was the weather, others say the economy was good while

still others say it was written in the stars, and it was just the right

alignment of people and planets to create the special things that occurred.

And so the summer of 1965 began down at the

crossroads, down the shore, the South Jersey Shore, where the crossroads was a

circle, the Somers Point Circle, and very close to where all the action would

take place and from where, as the sun set on Labor Day, everyone would leave to

go in their own new direction, for better or for worse, to reward or tragedy,

their destiny was determined - a fait accompli – but it still had to play out.